Programmers of All Backgrounds Find JavaScript Confusing

Without any prior knowledge of JavaScript, doing something as simple as declaring variables can be confusing. Or at least that’s what I found out when I was doing some internal consulting for another department of my old company. I was working with a seasoned pro, someone whose email signature read “Principal Consultant” and who was responsible for architecting entire, full-stack, standalone solutions for external clients that were required to seamlessly integrate with our existing products.

We would have occasional calls to discuss aspects of the project, and we’d often go back and forth via email. Then one day, I popped open my email client and saw an email from him. I liked to tackle his questions first thing in the morning because he lived on the East Coast, and I wanted to make sure I wasn’t blocking him from getting his work done. I read his email and eventually got to a section that read, “What’s the difference between let, const, and var?” I was initially taken aback a bit because such an elementary question to be asked by an engineer with probably twice the experience I had was shocking.

Then I realized this actually makes a lot of sense. JavaScript is confusing, and to have three different ways to declare variables can seem excessive (and it probably is). This pattern was only recently mainstream in the last 5 or so years with ES6, and for someone who hasn’t actively developed in JavaScript recently, the changes from ES6 would make JavaScript seem like an entirely different language from the versions that preceded it. JavaScript has a complicated history, so to understand “why” things are done the way they are, it would be helpful to understand how we got here.

A Brief History of JavaScript

The early web connected people in a way that was only possible in sci-fi films, previously. With that said, it was comprised of slow-loading, static pages that would be unrecognizable today. In 1993, the Mosaic web browser was created, and it allowed users to view web pages with their photos inline with the text (as opposed to in another window).

The lead developers for Mosaic founded Netscape, which introduced the incredibly popular Netscape Navigator. They started working on adding support for a scripting language, which they named JavaScript to ride the coattails of the hot programming language of the time: Java.

Microsoft entered the scene and introduced the Internet Explorer web browser in 1995 and effectively started the “browser wars.” Both web browsers began to support their own scripting languages to provide a richer, more dynamic web browsing experience to the end-users.

Having two main browsers with two separate scripting languages meant that web pages would often only fully function in one browser or the other. This fragmentation lead to the ECMAScript standardization in 1997. With the explosive growth of the internet, ECMAScript (i.e. JavaScript) became the defacto browser language and grew to incredible popularity.

Being commissioned with being a flexible scripting language while also being born in the shadows of Java made JavaScript a uniquely confusing language. JavaScript is weakly and dynamically typed but you can use the TypeScript superset of JavaScript to add strict typing. You can easily use both the Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) and Functional Programming paradigms in the same application. Because of its complicated history and its ongoing evolution, JavaScript remains one of the more popular but confusing programming languages to learn.

The var keyword

The var keyword is the oldest of the three keywords, and thus, it can be considered a little outdated. It has some odd behavior that can produce bugs without the proper knowledge or development environment configuration.

Scope

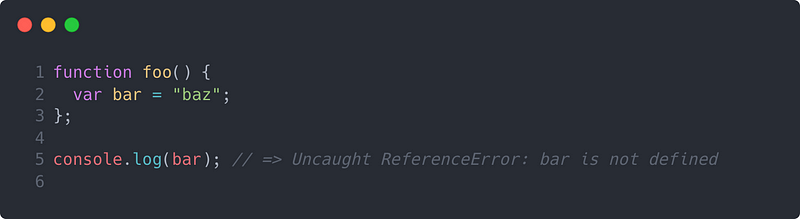

A variable declared using the var keyword is function scoped, unless declared outside of a function, then it is globally scoped. Take a look at the illustration below to understand function scoping.

The var variable above is scoped to the foo function, and therefore, it is not “visible” to the global scope around it.

Hoisting

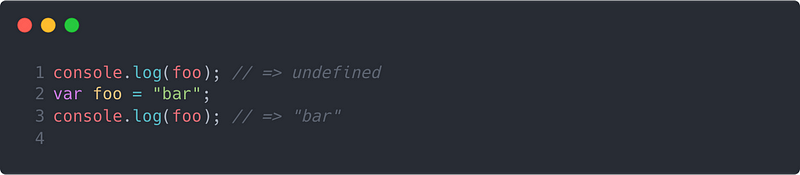

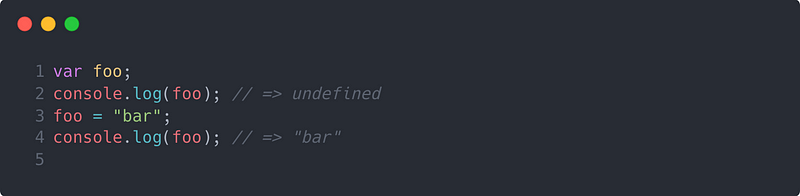

var declarations are hoisted and initially undefined before eventually being assigned. The JavaScript interpreter will hoist the declarations of function, variables, and classes and initialize them as undefined (with a few exceptions— keep reading). Thus, we can run the following code below without throwing an exception.

This might be a little confusing, so let’s explain what the JavaScript interpreter is actually doing. Before executing your JavaScript code, the interpreter will scan through and create a mapping of your declarations to optimize the code execution. For all of these declarations, the interpreter doesn’t assign the proper values because this would require executing code. Instead, it creates the mapping with all of these declarations assigned to undefined (again, with a few exceptions). Let’s illustrate this concept in code:

Declaration

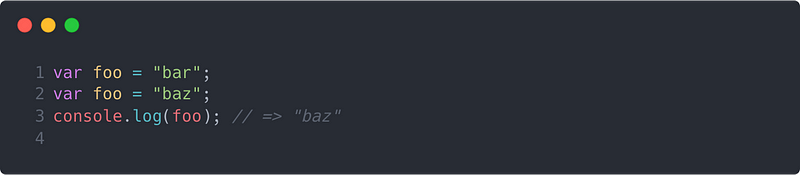

The var declaration can be re-declared. This is a subtle but powerfully dangerous concept that should not be overlooked because this feature allows you to introduce naming collisions into your code. Take a look at the example below:

This is a trivial example, but you can imagine how easy it would be to accidentally redeclare a variable in a much larger codebase. Modern development environments will allow you to configure a “linter” to warn you when you may have accidentally reassigned an existing variable.

The let keyword

The keyword let was introduced in ES6, and as this latest ECMAScript standard became widely adopted, let started to overtake var as the go-to keyword to declare variables. There are some main differences that make let a little less permissive, and therefore “safer”, than var.

Scope

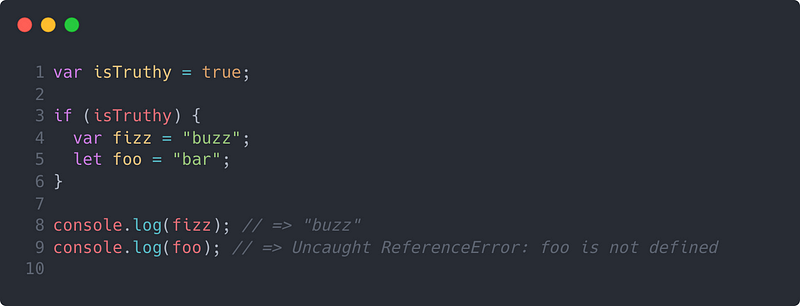

let is block-scoped, which is to say, it is scoped to its nearest containing block. So instead of only being scoped to the containing function block like var declarations, let declarations are scoped to the first containing block of all varieties. A block statement in JavaScript is any code in between a valid pair of “curly braces” (i.e. { and }). So, this includes if statements, for and while loops, function declarations, and even a standalone set of curly braces among other use cases. Let’s illustrate what I’m talking about here:

Hoisting

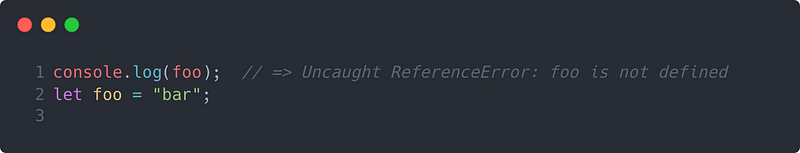

While all declarations are hoisted, let declarations behave a little differently than the hoisting described previously for the var keyword. Even though let declarations are hoisted, they are not initialized to undefined like hoisted var declarations are. This means that you can’t reference a variable that is declared using the let keyword before it is initialized.

This scenario illustrates a quirk that is referred to as the “Temporal Dead Zone (TDZ).” This is a temporal issue because it has to do with timing. Since the variable is not initialized until its first assignment during runtime, an error will be thrown if you try to reference it prematurely.

Declaration

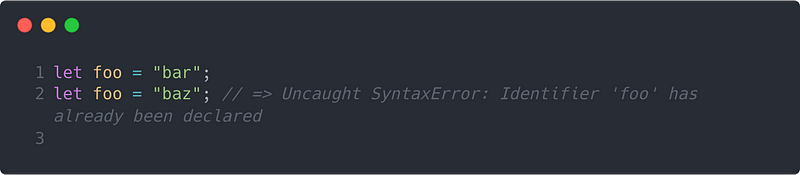

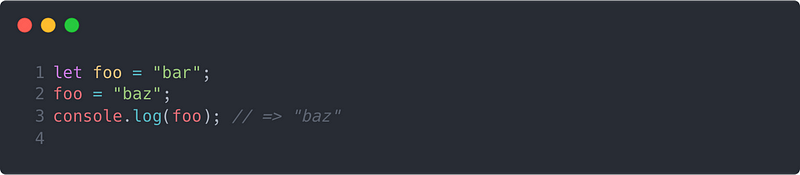

Another way the let keyword is less permissive than var is that it can’t be redeclared. Redeclaring in general is a bit of an odd feature of JavaScript, and designing it out of the let keyword was a major win. Here’s an example of what I’m talking about.

To be clear, redeclaration and reassignment are two different things. You can definitely reassign let variables as you normally would expect. They wouldn’t be very good variables if they couldn’t vary.

The const keyword

The const keyword is yet another way to declare variables. As the name would imply, const declarations can be effectively referred to as “constants.” Let’s break down their behavior.

Scope

Much like the let keyword, const declarations are block-scoped.

Hoisting

Hoisting for the const keyword behaves exactly the same way as the let keyword. It is hoisted but uninitialized, and therefore, it will experience the same Temporal Dead Zone issues.

Declaration

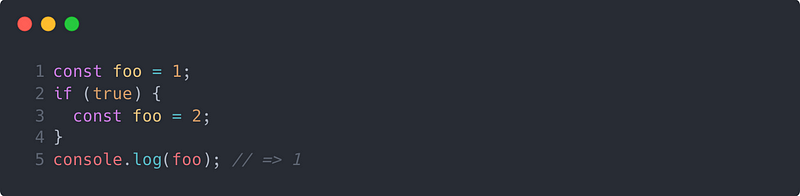

You can’t redeclare a const declaration once you’ve already declared it. Again, this is the exact same behavior as with let declarations. However, because lets and consts are block-scoped, it may sometimes seem like they are being redeclared when they actually aren’t. Take a look at this example:

You’ll notice that we declare and assign the foo constant twice, but the execution of our code will not throw an exception. Again, this is because of the block scoping nature of const declarations.

Assignment

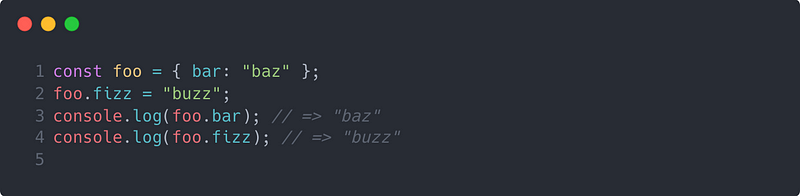

The main feature of the const keyword is that it can’t be reassigned. Therefore, you must immediately assign a value to the constant, otherwise, that constant will remain undefined. One notable “loophole” can be seen below:

Even though foo is a constant, the code above does not generate an exception. Can you tell what’s going on here? Take a second to think about it.

Although it appears that we’re violating the primary feature of the const keyword, strictly speaking, we aren’t actually reassigning the foo constant. This is because we are using the Object data structure. So we initialize foo to an Object instance, and at every step of the way, foo is always referencing that same Object instance. We are simply adding another property to that object instead of reassigning foo.

When to Use Them

You should use whatever you feel comfortable with, but I like to only be as permissive as is required. If your value will never need to be reassigned, use const, otherwise, use a let. I never use vars anymore because they are too permissive. If I ever need to reference a variable outside of its scope, I simply move the variable declaration to a higher, common scope. I’ve also never had a reason to take advantage of var’s lack of a Temporal Dead Zone, and in fact, I see that attribute as more of a bug and not a feature.

Conclusion

Even experienced developers can find JavaScript confusing at times. Its unusual history makes it one of the most popular languages today, but also one of the most difficult to master. Developing a thorough understanding of var, let, and const is an important step to building a strong JavaScript foundation.

Michael has a diverse background in software engineering, mechanical engineering, economics, and management. After a successful career in mechanical engineering, Michael decided to become a software engineer and attended the Hack Reactor coding bootcamp. Michael enjoys writing about his experiences and helping others start their journies in software development.